There was once a disciple of a great Guru.

Day after day, the disciple would sit at the feet of his teacher

listening to his instruction.

Many people would come to visit

and inevitably, the teacher would engage them

by telling a story.

One day, the disciple asked;

"Guruji, why do you engage people by means of stories?

Why don't you just give them your teaching straight out?"

The teacher answered

"Bring me some water."

Now the disciple knew his teacher to be a very formal and disciplined man.

He had never asked for water at this time of the day.

Nevertheless, he went immediately to fetch it.

Taking a clean brass waterpot from the ashram kitchen,

the disciple went to the well,

filled the pot with water and returned.

He offered it to his teacher, who then spoke

"Why have you brought me a pot

when I asked only for water?"

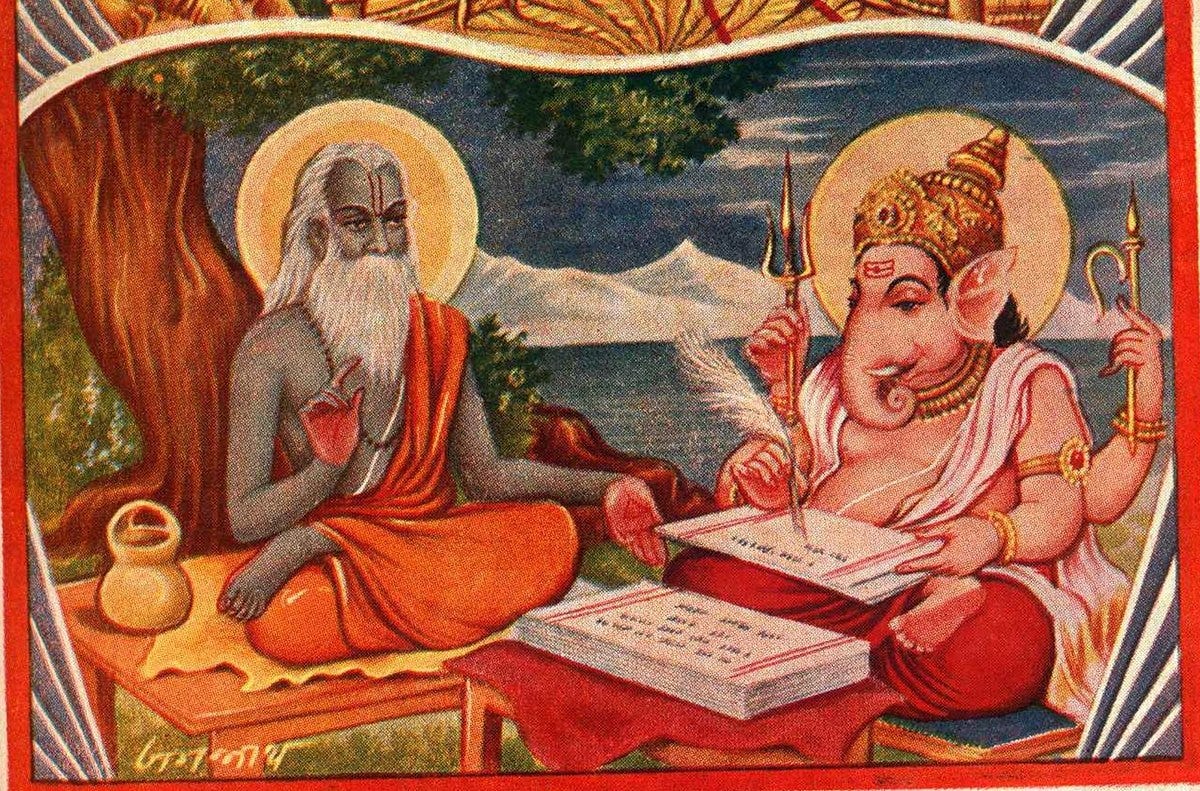

There is an aspect of this story that is often overlooked. I am reminded of when the Vedic Sage Vyasa wanted the great epic, the Mahabharata, to be written down. Looking for someone who could do the writing, he chose Ganesha, a being of great intellect and Viveka, or discrimination.

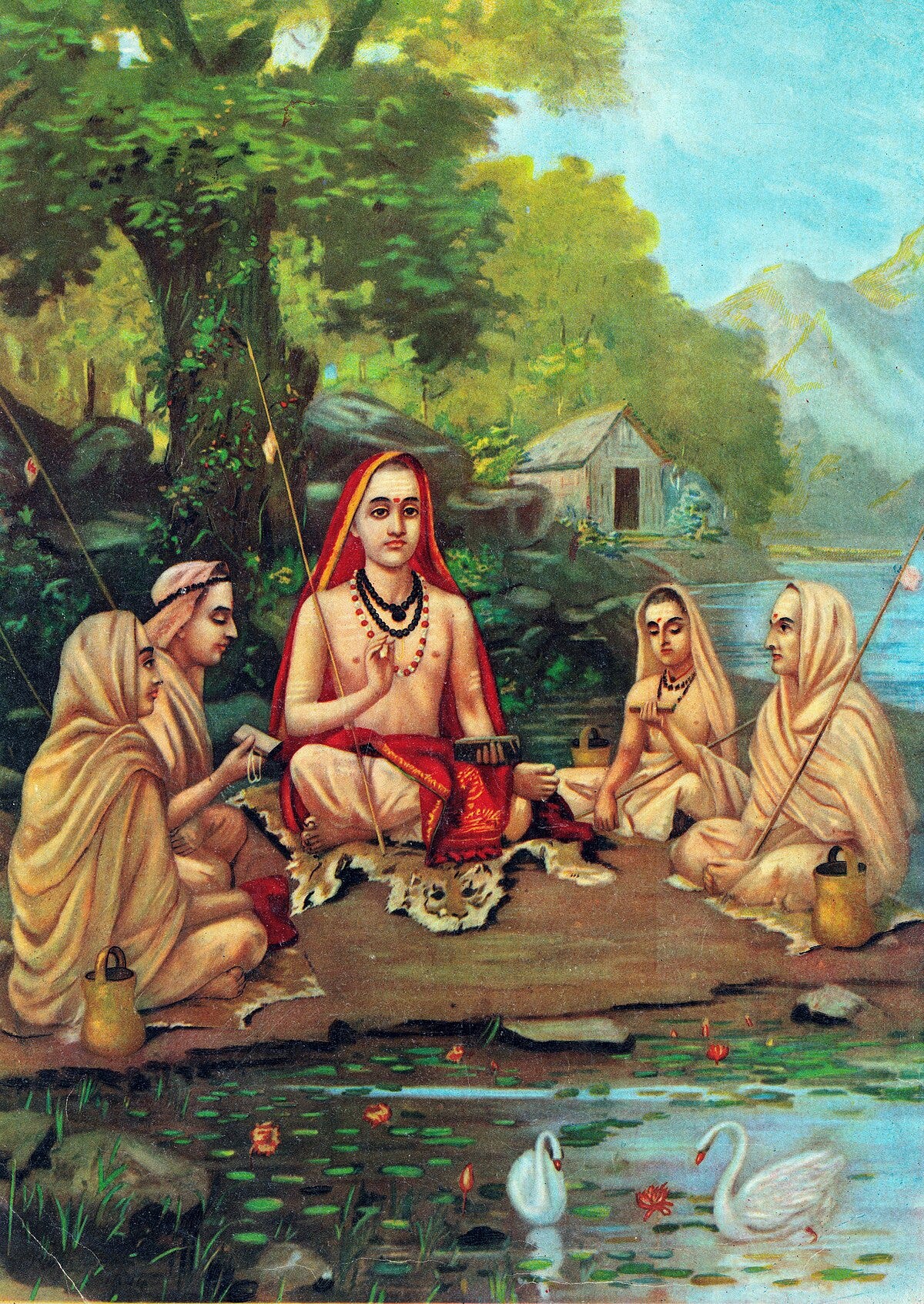

Vyasa dictating the Mahabharata to Ganesh

It is said of the Mahabharata, the largest epic story in the world, ‘If it isn’t in the Mahabharata, it isn’t.’’ Faced with this grand work, Ganesha said that he would undertake the task of writing it all down, but only if Vyasa did not pause in his telling of the story; and he also said he would not write down anything he did not understand. This agreement required Vyasa to be extremely focused and clear in his exposition. However, for Vyasa, to talk without pause would be impossible, so he would speak about subtle and profound Truths, causing Ganesha to stop writing as he needed time to understand. Vyasa used that time to prepare the next part of the story.

Ganesha symbolizes intellect, discrimination, and the power to remove obstacles. He represents the necessity of wisdom and understanding in the expounding and receiving of knowledge. After all, a text that is not understood is merely noise.

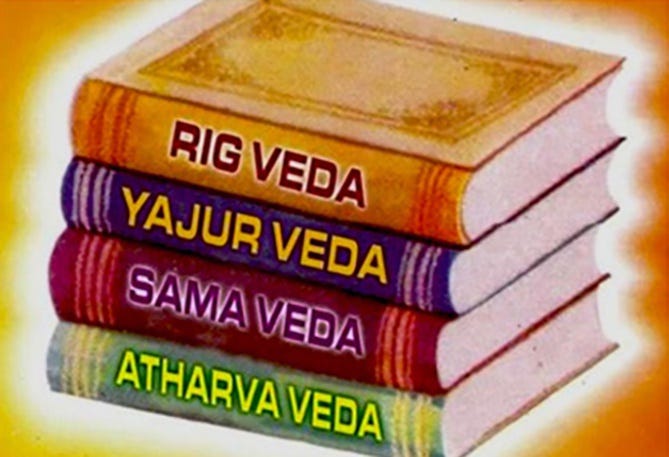

As for Maharishi Veda Vyasa, he was drowned in the vast ocean of the Veda, encompassing the knowledge of the ultimate ‘Truth.’ It was Vyasa who compiled the Vedas into four sections and arranged the Puranas.

The Four Vedas

He wrote the Brahma Sutras and dictated the Mahabharata, India's great epic, which includes the Bhagavad Gita, and is the longest in the world. His vast knowledge came from the boundless nature of Divine inspiration and wisdom.

Brahma Sutras

Vyasa and Ganesha together represent ‘Revelation’ and ‘Comprehension’; and both are necessary. The ‘story’ is contained in the cup, and the Vidya or Knowledge, what is contained in the cup is the story, but what is not considered in this short story above is the qualification of the one who hears the instruction. This ‘qualification’ is called ‘Adhikharbheda’ or ‘the qualification of the aspirant’ (or hearer) of the story or instruction.

For Shankara, the highest teaching of Advaita – “Brahman alone is real, the world is illusory (Mithya), and the individual soul (Jiva) is none other than Brahman” (Brahma Satyam, Jagat Mithya, Jivo Brahmaiva Na Aparah) – is only truly meaningful for those with the highest adhikara or qualification. Advaita was not a teaching to be believed or assumed, like putting on a mask or imitating a mood. The Realization of the Self is something that can not be imitated or assumed. It is a distinct state of consciousness, a qualification that needs to be realized. To me, this is humbling knowledge, as I had been trying to imitate the qualities of an enlightened man. It was Maharishi who brought me out of that state.

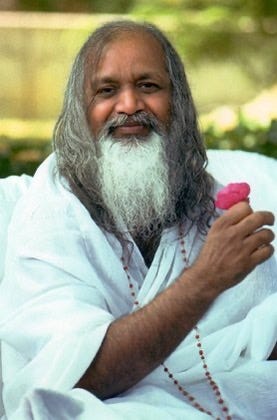

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

In 1972, I attended an 8-month-long meditation course (in Mallorca, Spain, and Fiuggi Fonte, Italy) and became a teacher of Transcendental Meditation. During this time, Maharishi often spoke of the Seven States of Consciousness. Each State of Consciousness had different Adhikarbheda or qualifications. I will briefly define them, as I think they offer insight into the understanding of Religious practice and Advaita Vedanta.

The first three states of consciousness are 1) Waking, 2) Dreaming, and 3) Sleeping. 4) The Fourth state is Transcendental Consciousness, when only the subjective state of Being seems to exist. This is only temporary and one comes out of it. 5) Cosmic Consciousness, is the permanent establishment of Transcendental Consciousness along with the ever-changing states of waking, dreaming, and sleeping. 6) In this highly refined state, there arises Divine Love and devotion as the perception of God as ‘other’, as Divinity or a God-like quality becomes apparent even on the level of the senses. 7) Unity Consciousness, identification as Everything, No limits, No self, No other. Not one God or many gods; Only God. Advaita Vedanta is primarily concerned with the Sixth Stage and the Sixth to Seventh Stage transition.

Maharishi once said, “We live in a state of Unity in Ignorance (waking, dreaming, and sleeping). In meditation, we transcend the senses into a temporary state of Unity (devoid of the world), which we again come out of. When the Transcendental state of Consciousness permanently coexists with waking, dreaming, and sleeping, we have entered for the first time into a state of Duality, or Cosmic Conciousness. It is at this point that Vichara or Inquiry can take place. This is because, for the first time, we have achieved duality. Without this duality, inquiry, according to Maharishi and Shankara, is fruitless (aphala) and does not bear fruit. That qualification is laid out in Maharishi’s Seven States of Consciousness.

Going back to the original story above, no matter what is said, instruction, scripture, or Truth will not be properly grasped by a person who is not qualified. Adhikarbheda is a fundamental concept in Hinduism, particularly in Advaita Vedanta. It literally translates to ‘difference in qualification’ or ‘difference in eligibility.’

People have different levels of Adhikarbheda. For Shankara, Adhikarbheda ensures that individuals are guided to the spiritual path most suitable for their current state. Shankara called Vichara, or inquiry, the ultimate tool for liberation, but he said the practice of Vichara is reserved for those who have sufficiently prepared themselves, which seems to be a very rare state.

Shankara with his four main disciples

Krishna instructing Arjuna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra in the Bhagavad Gita

There is a famous verse in the Bhagavad Gita where Krishna says: “Because one can perform it, one’s own Dharma is better than the Dharma of another. Better is death in one’s own Dharma, the Dharma of another brings danger.” In other words, there are situations worse than death; to waste one’s life (in a practice one is not qualified for) is a fate worse than death. The reference to “one’s own Dharma” is a recognition of the principle of Adhikarbheda. Attempting to mentally replicate or emulate a higher state of consciousness is fruitless and a waste of life.

I am reminded of my first instructions in Ayurveda at Kalidas Sanskrit University. The teacher addressed the incoming class and said, “Everything is medicinal and everything is poisonous, and Ayurveda will teach you how to tell the difference between the two.” What could this mean? Here is an example:

Because of the differing elemental qualities in a person by birth, experience, time, location, season, etc., different elemental qualities are increased or decreased in a person. For example, Oprah Winfrey has very marked elemental qualities from birth (she is water/earth predominant/ KAPHA)

Oprah Winfrey

This is compared to Audrey Hepburn who is air/ether predominant/ VATA).

Audrey Hepburn

Each of these women, in their attempt to gain or maintain health or Sama (Balance), needs to use opposites (to their birth and/or presently elemental qualities) in their food and lifestyle. For example . . . in general, raw foods would not be balancing for Audrey Hepburn, but they would be for Oprah Winfrey. Ayurveda is not idealistic. It is practical.

Adhikarbheda ( considered here in terms of religious practice) is also not idealistic; it is practical, recognizing and accounting for the differences or qualifications of the person in terms of states of conciousness and appropriate practice. For instance, Karma Yoga and Bhakti Yoga are suitable for most people, rather than inquiry or Vichara.

So, there is the container of the story, the ‘pot’ in the recorded story above. There is the water or what is carried in the pot; the meaning, instruction, knowledge, or ‘Vidya.’ And finally, there is the one who hears the message or story brought in the pot; it is here that the concept of Adhikarbheda must be taken into account.

So, the next time the Guru asks you to fetch some water . . .