The Man Who Created the Taj Mahal

For my mother who told me my first story, and my father who told me what it meant . . .

Introduction

The story told here is a true lie . . .

In India, folk tales gather around extraordinary events, places, and people like moths attracted to light in the dark, especially if much time has passed, which it has in the oldest civilization in the world. There are so many narratives about everything, and it is impossible to know if what we hear is made up or really true.

Still, the light of a story can be beautiful all by itself, and the radiance of this particular story, not its verity, was what attracted my attention and inspired me to write it down.

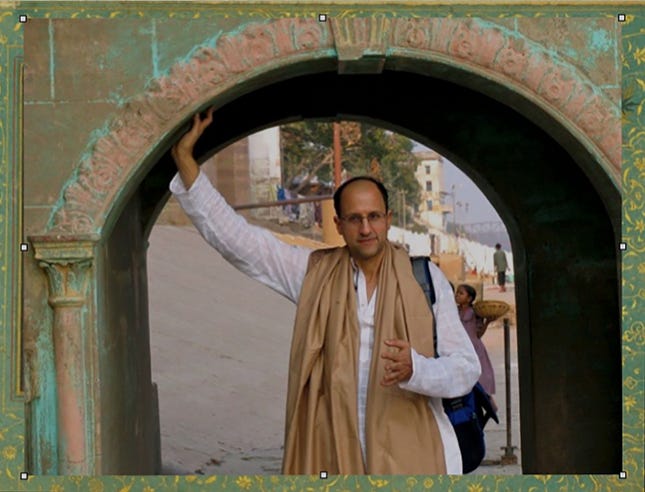

In 2004 I spent the winter in Benaras, the oldest still-living city in the world. One evening, as I walked along the stone ghats that run for miles along the Ganges, I fell into conversation with an aged sadhu who told me a story about the man who designed the Taj Mahal. He described the incredible drama of how the building was created and what lay at the root of its subtle and harmonious beauty.

As far as I know, this legend exists only in the oral tradition of India and has never been written down before. It went something like this:

The Man Who Created the Taj Mahal

Shah Jehan ruled India as the fifth Mughal Emperor from 1628 to 1658

When Shah Jehan was at the height of his power, it was brought to his attention that a great artisan, especially gifted in architecture and sculpting, existed in his kingdom. This man had a gift: he could create the exact likeness of any person merely from seeing their hands. It was said that from a moment’s study of a person’s palms and fingers, this artist could create their exact likeness in stone.

Shan Jehan ordered that the man be brought before him. “Is this true? Can you create the face of a person from a glimpse of only their hands?” the Shah asked.

The artisan, who was very proud of his ability, replied, “This is indeed true, O’ Shah. All things are related, one to another, and I can perceive some of them!”

Then, the artisan offered a breathtaking challenge to the Shah: “Let all the unmarried women of your court be brought forth in this room, and place them in a row all together. I will walk down that line of women and, from their midst, select the most beautiful amongst them. Then, I will carve her likeness in stone.

“If I succeed in your eyes and the eyes of the court in creating a perfect image of this woman with all her subtlety and manner, then she shall be given to me as my wife for reward. If I fail to create her perfect image, then let me be killed.”

Shah Jehan was amazed at the boldness of the sculptor and filled with excitement for his proposal. He immediately ordered the assembly to be gathered together.

In little more than an hour, all the unmarried women of the court were brought before the artisan, each one heavily veiled as was the custom of the day and all in anticipation. They held out their hands for the artisan to inspect as he walked slowly by.

Now, a high-born maiden related to Shah Jehan had heard of the incredible challenge of the artisan and, being greatly excited, had inserted herself into the line of the assembled women. And, as fate would have it, it was in front of this most beautiful young girl that the artisan stopped and said, “This is the woman whose face I will sculpt in stone!” He had seen her perfectly in her hands and had fallen in love.

Shah Jehan was told immediately that the woman was related to him, and he was deeply concerned, but he decided to do nothing for the time being and instead sent spies to watch and note the progress of the artisan.

The artisan was given a suite of rooms at the Agra Fort, and he set to work. After a week the Shah’s spies reported back to him that the artisan was sculpting an exact likeness of the woman. Several more times, the spies were sent out, and the news returned that the image in stone was, without a doubt, the young woman in all her beauty and radiance.

Finally, her image was completed and, in front of the assembled court, unveiled, with gasps of wonder and admiration, at this man who could sculpt every detail of a woman by seeing only her hands.

But Shah Jehan was troubled. This young woman had been secretly promised to the general of his army. He could not give her to this artisan! The Shah spoke to him before the court: “I am deeply impressed with your skill, artistry, and intuition. You have, indeed, created an exact and most beautiful image of this woman who happens to be my relative. But you must choose another woman! You cannot marry this princess. She has been promised to another man.”

The whole assembly stood without breathing. All were deeply troubled. Their ruler could not honor his promise. Many among them felt deeply embarrassed.

But the artisan replied, “Great Shah, I have picked the most beautiful candle from the tapers of your court. It is her flame that lights the lamp of my heart. It is her face that delights my eyes. It is in her form that I revel. It is her and her alone. If you will not honor your agreement, then I have nothing to do but leave and wait upon the will of Allah.”

Upon saying that, the artisan bowed and proudly walked from the assembled gathering.

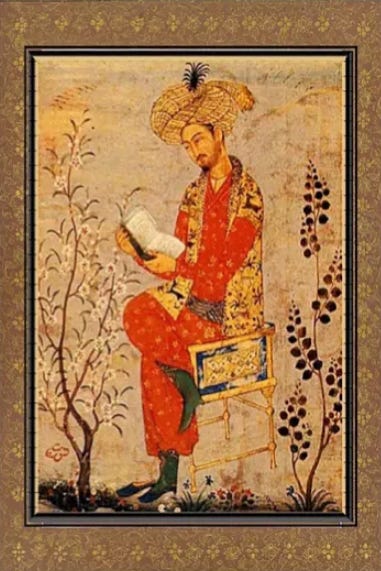

The palm reader, scholar, architect

Many years passed, and Shah Jehan grew older. Then, the death of his favorite wife, Mumtaz, eclipsed the bright sun of his life. His heart was broken, and his soul fell into despair.

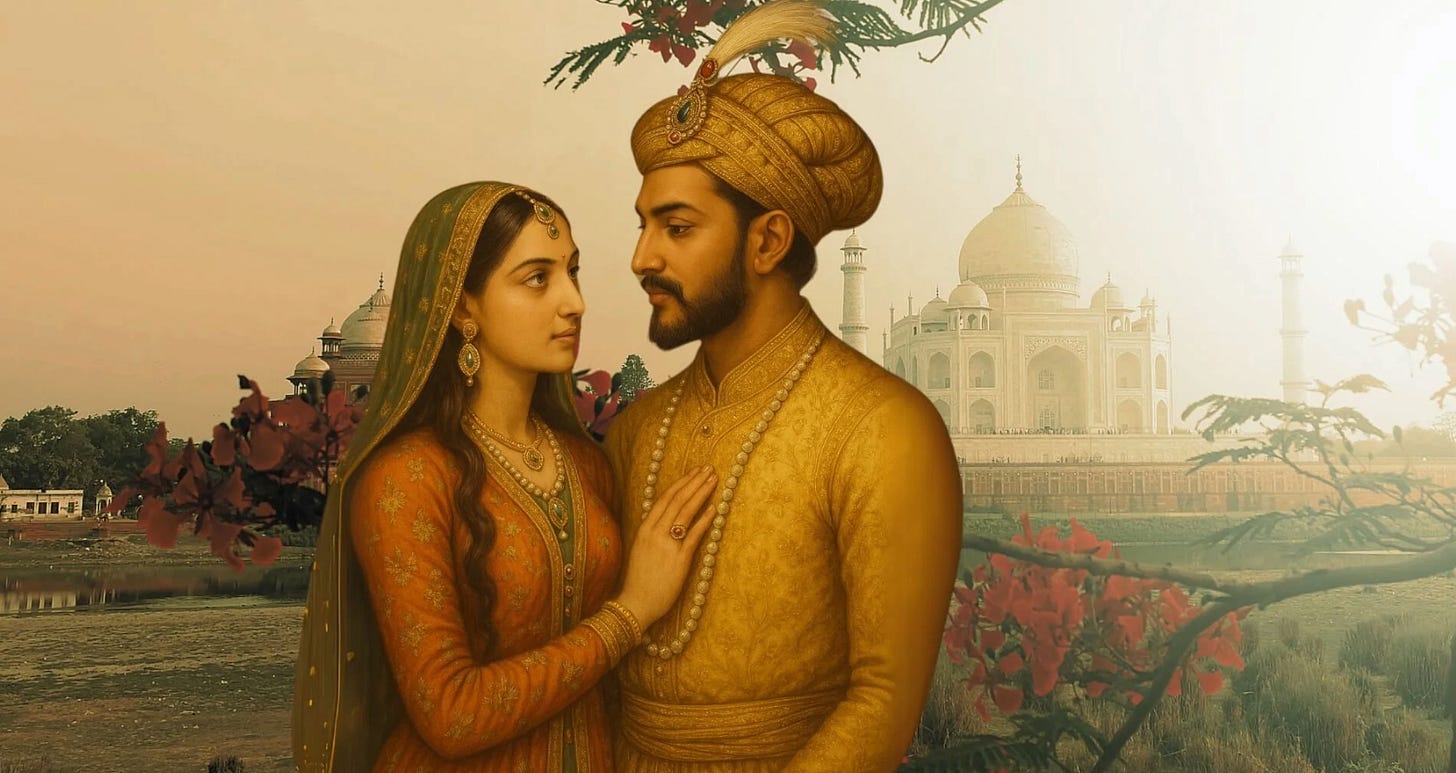

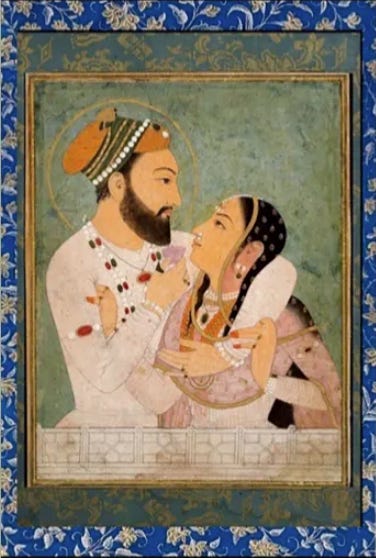

Shah Jehan and Mumtaz with the Taj Mahal in the background

The horse of his longing grew wild with the remembrance of his wife, and a yearning to eternalize her presence in the most beautiful and perfect mausoleum came to fill his life.

The passing of Mumtaz Mahal. In the immediate aftermath of his bereavement, the Emperor was reportedly inconsolable. After her death, Shah Jahan went into secluded mourning for a year. When he appeared again, his hair had turned white. His back was bent, and his face was worn.

The Shah was inflamed with a desire to build a tomb for his wife to rest in, a symbol of the grand memory of their relationship, the inevitability of their separation in death, and the eternal glory of God. It was also to be the burial chamber in which he, himself, would be laid one day by her side.

But who would design this building? Who could create and structure the paradoxical feeling of his heart in stone? Shah Jehan’s thoughts went again to the artisan he had summoned many years before. The artist had become an architect who designed many of the most beautiful mosques and buildings in the land. Everywhere, he was spoken of with admiration and praise. Surely, this was the man to take on this extraordinarily special and emotionally laden project.

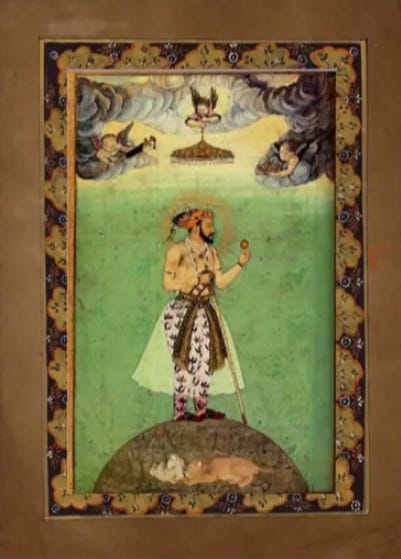

Shah Jehan, bestriding the world

Again, the architect was found and brought before the Shah, who spoke to him as follows: “Noble man,” he began, “In the name of Allah, please accept my request for your help in designing a mausoleum for my now-deceased wife, Mumtaz Mahal, on whom there may be peace. You were dishonored by me at our last meeting together. I now wish to set that matter aright.

“This beautiful girl, the very same one whose image you carved so exactly in stone, is still unmarried. My general, the man she had been promised to, was slain in battle. As a token of my sincere wish to engage your services, accept her in marriage. She is yours upon the fulfillment of my request: design the most beautiful building in the world, a mausoleum for my now deceased wife, Mumtaz, on whom there may be peace, and for myself.”

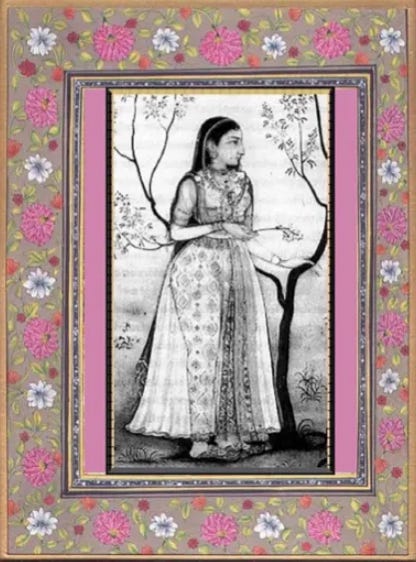

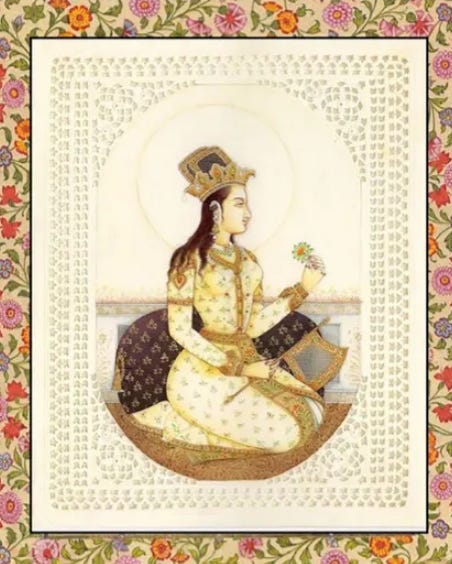

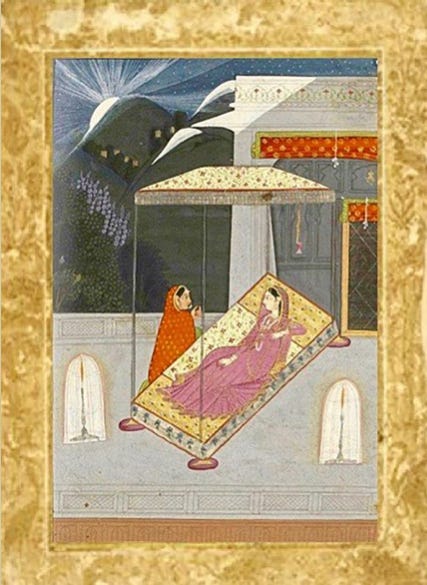

Mumtaz Mahal

The architect was astounded, greatly pleased, and highly honored. Indeed, no one had ever seen the Shah so in need before someone. The architect exclaimed, “Noble Ruler, Glory of Islam, I am honored to accept your gift and will immediately begin the design of the mausoleum. By the grace of Allah, it shall be done!”

He was given a suite of rooms in the Agra fort and, in a state of great inspiration, immediately began drawing up plans for the mausoleum. Within a few weeks, the shape of the building was ready and brought before the Shah. But he was not at all pleased. The feeling of the structure was not right. Undaunted, the architect drafted more plans, this time using a different style of construction. His energy was great and shining; he worked fervently, touched by the future promise of the young lady to be his bride.

Again, the drawings were brought before the Shah, and again, they were rejected. The process repeated itself many times until the architect began to despair. He would never be able to have the lovely girl as his bride unless Shah Jehan accepted his design, and it seemed to him as if that would never happen.

Now the Vizier, one of the wisest aides to Shah Jehan, approached him and offered a suggestion: “Oh noble Shah, please give your attention to my humble idea. By the grace of Allah, I have seen a way to attain your desires.

“Presently, your architect is unable to produce a suitable plan for the mausoleum because of his inability to feel what you feel. There is a vastly different state of mind and emotion between you and your architect. You, my Lord, after years of joyous love, are in a state of grieving for your wife, Mumtaz, on whom there may be peace. The architect is feeling a state of joyful anticipation of seeing his future wife and entering into the happy state of marriage.

Because he does not feel the complexity of emotion that you feel, he cannot create what you desire.

“I believe this disparate state of emotions is at the root of the lack of a suitable building plan for the Mausoleum.”

“Here is what I suggest be done: Let it be known to the architect that his intended bride is ill and in bed; indeed, tell him that his young lady is sick and near death. Inform him that she yearns for him and has done so since she first saw him. Bring this news to the ears of your architect. Let his heart also be filled with yearning, grief, and sorrow.

“This will bring balance to his now too-happy heart and allow the emotional state of the architect to duplicate the feelings of your heart and create what your eyes yearn to see.”

Shah Jehan was pleased with the proposal and gave his advisor full authority to do what he had suggested. Quickly, the Vizier went to the architect's rooms and told the story that he had laid before the Shah.

The architect was heart-rent by the news. He was shocked, saddened, and humbled by the tragic sense of his life and of life itself. So much beauty, so much sorrow, so much hope, so much despair, his heart broke open, and tears ran freely from his eyes. He did not know whether he was crying in sadness or ecstasy.

All his life, he had remembered the young woman whose hands he had seen, whose image he had created, whose heart he cherished. He must be with her before she passed beyond this world.

He threw himself into the plans with a broken heart. He worked in a frenzy of love. One could not say whether he was happy or depressed. His heart coursed with joy and sorrow, hope and despair, and the tears of all these emotions fell upon the pages of his drawings. His hands gave form to his full-feeling heart, and in this way, the Taj Mahal was created.

In the end, Shah Jehan received the plans for the most beautiful building in the world; the architect was joined in marriage to his beloved, and all of them, now dead, live on in the story and building of the Taj Mahal.

Ehvam – Thus, I have heard . . .

Shah Jehan wrote the following description of the Taj Mahal:

“Should the guilty seek asylum here, like one pardoned, he becomes free from sin. Should a sinner make his way to this exquisite building, All his past sins will be washed away. The sight of this palace creates sorrowing sighs, And here, the sun and the moon shed tears from their eyes. In this world, this edifice has been made To display God’s Glory.”

As he grew older, Shah Jehan chose his oldest son, Dara Shikoh, to succeed him as the Mughal Emperor of India.

His younger sons, also children of Mumtaz Mahal, the woman for whom the Shah had built the Taj, disputed the choice of their father and went to war with each other for the throne. Although Dara was supported by his father, the second-eldest son, Aurangzeb, defeated and killed his other brothers and imprisoned their father at Agra Fort.

There, Shah Jehan spent the rest of his life as a prisoner, attended by his oldest daughter, Jehanarra. From his room at the fort, off in the distance, he could see the Taj Mahal, the resting place of his beloved wife, Mumtaz, and it is said that he died gazing at this monument of love, life, loss, and God.

The death of Shah Jehan, supported by his daughter Jahanara, looking at the Taj Mahal from a window at the Agra Fort.

After the death of Shah Jehan, Aurangzeb had his father buried in the Taj Mahal alongside his beloved wife. Their bodies lay there together to this day.

The burial vaults of Shah Jehan and Mumtaz Mahal

UNDERSTANDING and The TWO WINGS of the BIRD

It has been said that the bird of Wisdom has two wings. One wing is experience; we must experience something to know it. But experience alone is not enough. The other wing is Understanding; we must understand and have a story for what we have experienced. Without examination, understanding, and a proper or correct explanation of experience, experience is often misleading.

In the Vedic tradition of ancient India, the education of young people was mainly by rote memory. It was thought that a student should first hear and memorize the stories and knowledge of the scriptures, and then, later in life, that knowledge and story would come to the person to support and inform his experience as he journeyed through life.

This story is patterned on that tradition. The first part presents ‘experience’ in the form of a story. The second part, which follows below, is an examination and discussion of the experience. It is a consideration particularly relevant to adults because its message needs maturity to understand, one born of the frustrations and failures of a life lived beyond childhood and adolescence.

An interpretation of the story

A monk is walking down a road in the medieval English countryside when he comes upon a group of men working with rocks. He goes up to the first man and asks, “What is it you are doing here?” The worker replies, “I am placing one rock on top of another.”

Proceeding further, the monk comes upon another man and asks him the same question, “What is it you are doing here?”

This man replies, “I am building a wall.”

The monk continues further down the road and asks a third man, “What is it that you are doing here?”

This man replies, “I am building a cathedral.”

Not every one of us has the same understanding of the task we are performing. Some of us are merely carrying rocks, some are building a wall, and some are creating a cathedral. Like men working with rocks, there are different understandings of ‘The Man Who Created the Taj Mahal.’ What follows is one of them . . .

I owe my insight into this story to my teacher, Adi Da Samraj. In his lifetime, he undertook an in-depth, wide-ranging, and brilliant consideration of the religions and cultures of the world. On several occasions, he spoke about the Taj Mahal as a structure whose design was uniquely full of meaning:

The Message of the Taj Mahal

Adi Da wrote: “The message of the Taj Mahal is a message about Enlightenment, about the Enlightenment of the whole body. The Taj Mahal is a burial place, but its message is Life. The secret of Enlightenment is resurrection, the incarnation of love, and freedom from death.

“The spiritual problem of Shah Jehan, the Mogul Emperor of India who built the Taj Mahal as a tomb for his favorite wife, is the mortality of the loved one. All the conditions for our ultimate Realization are present in the form of our relations, but they are confounded by mortality. Having discovered that the loved one is mortal, you must commit yourself heroically to the service of his or her immortality. You can love what is dying, but you can only be in love with what is already Transcendental. The process of your loving is confounded until you overcome death, not philosophically, but bodily, through bodily and Transcendental Enlightenment.

“The Enlightened man reveals his Enlightenment through bodily signs. Like the Taj Mahal, the body of the Enlightened man is a perfect balance between the descending and ascending forces of manifest existence.

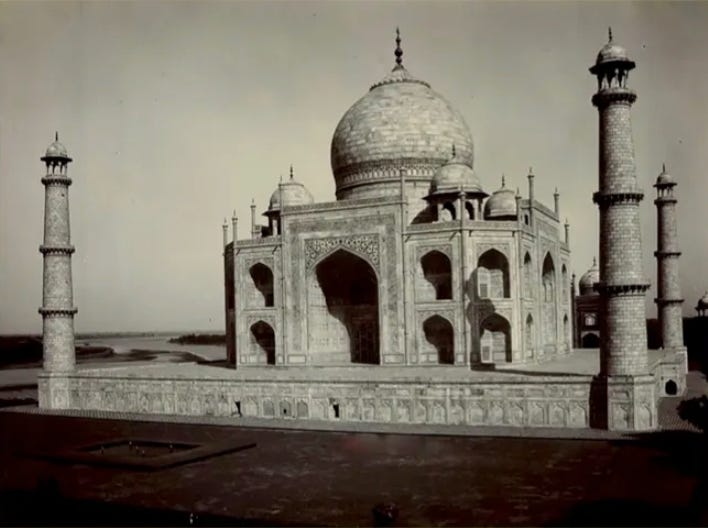

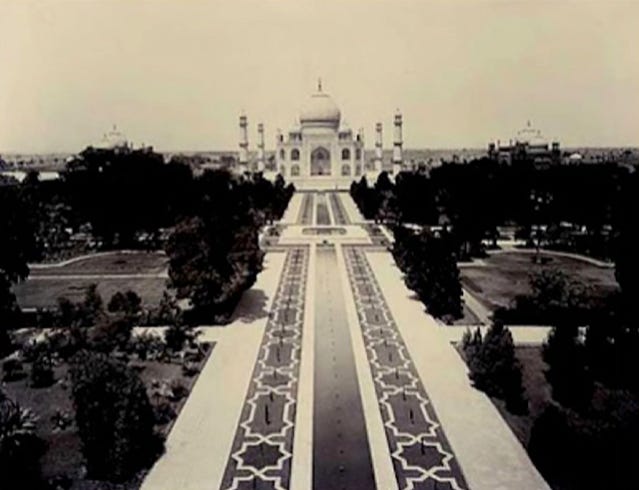

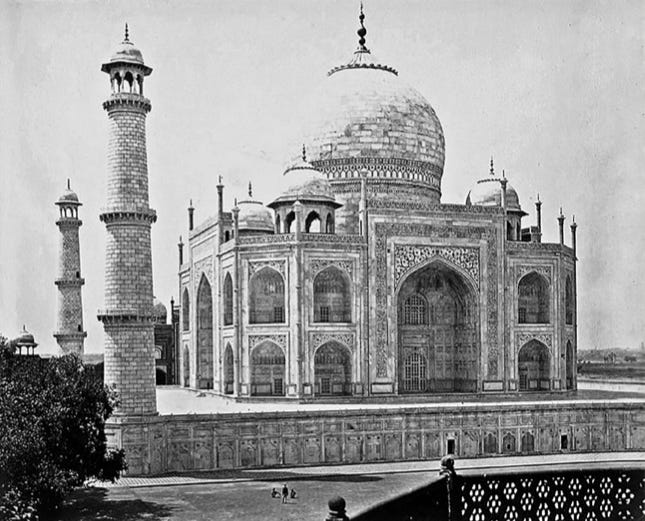

“Photographs of the Taj Mahal generally do not convey this perfect balance because they confine the image within a frame. However, when the Taj Mahal is viewed in the undefined space at the center, it is one of the most perfectly balanced visual perceptions in the world. The two forces, descending and ascending, are perfectly equal.

“The Taj Mahal is a description of the whole body. The body in its Enlightenment, the body when it is beautiful in Truth, is a perfect balance between what descends and what ascends. When there is too much attention to what is descended and only physical or too much attention to what is ascended and only psychic, such imbalance yields mortality and delusion. Only the harmony is immortal and conducive to Illumination.” - Adi Da

I will use my teacher’s commentary to illuminate this story, ‘The Man Who Created the Taj Mahal.’

A Summary of the Story

In the story told above, after the artisan received the commission from Shah Jehan to design the Mausoleum, he was given a suite of rooms at the palace, where he set to work with great excitement. He had the capability to fulfill the commission; after all, he had done many other beautiful buildings in the realm. But with this particular job, he felt like God had smiled upon him . . . the Shah had apologized for what had transpired years ago and wished to “make things right.” Now, he was to be paid not only with gold but with the gift of the young woman he had loved ever since he first saw her . . . in her hands. Thrilled with radiant possibilities, in little more than a month, he created his first proposal and presented it; it was turned down.

The architect was disappointed, but this was not the first time he had failed to design what his client wanted, so undeterred, he again set to work, and this time, after two months, he produced several more plans, but they too were rejected. After two more months, he produced even more additional plans, but they also were rejected.

Months went by, and even more submissions were rejected. When the architect inquired, “What is the problem with the plans?” the Shah said they were too grand and glorious. So, the architect lessened the soaring grandeur of the building and presented his drawings again. Then, he was told these new plans were too reminiscent of death. He could not match his creative skills with the feelings of the Shah. It was a skill he had prided himself on, but now, for the first time in his life, and in spite of all his efforts, he was not able to please his client, the Shah. I believe this failure had something to do with balance. Remember what Adi Da had pointed out:

“The Taj Mahal . . . is a perfect balance between what descends and what ascends.”

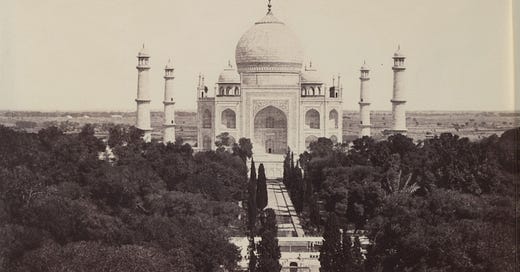

The Taj Mahal

Let us consider this further:

‘Sama’ or Balance

In Sanskrit, “Sama” means ‘balance.’ The word “Samadhi” means balanced (sama) vision (dhi) and indicates a state of being that is neither inward nor outwardly turned; rather, it is balanced. The word ‘sama’ corresponds to “health” in Ayurveda; it represents the dynamic balance of a person and his or her particular condition in an ever-changing environment and time. ‘Sama’ is not a fixed ideal; rather. it is a living, dynamic (ever-changing) balance in any and every particular environment.

What was Wanted and What went Wrong

The architect was filled with the enthusiasm and idealism of the promise of romantic love. But this bright, rosy aspect of love was not what the Shah felt or wanted in his building. The Shah had certainly experienced such love with his wife Mumtaz, the woman whom he wished to memorialize in the Taj, but she had died. And, too, he had grown older, and there was trouble in his kingdom. A different meaning of what life was about, of what love truly is, had come upon him.

In the Taj Mahal, the Shah sought not merely to make a temple of romantic love but also to acknowledge death and the failure of all things to persist over time. He wanted to memorialize not only Mumtaz and their love, but to build a temple to what is eternal. He envisioned a more comprehensive truth, the Reality of life as loss in the presence of eternity or God. As Adi Da writes:

“Having discovered that the loved one is mortal, you must commit yourself heroically to the service of his or her immortality. You can love what is dying, but you can only be in love with what is already Transcendental.”

The story tells us that the architect, in his romantic enthusiasm for what he was to gain, had lost touch with the inevitable death of a loved one and was, therefore, unable to create the perfect or balanced plans for the Taj Mahal. It was not until the Vizier of the Shah pointed out the root of the problem and the architect was told that he might never be able to see the love of his life because she was sick, that his heart broke open, and he gained balance. This ‘balance’ was the seed of what became the Taj Mahal.

The vast majority of people describe romantic emotions when they behold the building. How often have I read about the Taj Mahal and heard, “The Taj Mahal is the undying symbol of true love.” But what does this mean?

The Lesson of the Story

While the architect could mold every aspect of a woman by seeing only her hands, he could not duplicate the vision of the Shah because he did not have the experience or the understanding of what was lacking. The prejudice of love and desire blinded him. In this tale, the architect must overcome the deluding effects of romantic love. We could even say romantic love is a sin that must be transcended.

“Hamartia” is the word that translates as “sin” in the Bible. It means “to miss the mark.” The architect was ‘missing the mark’ and, like most of us, not aware of doing so. His ‘sin’ was subtle and ‘benign’ . . . not born of hate or evil intent, but springing from infatuation and the yearning of desire. It blinded him to the tragic side of life, the inevitability of death and separation. Throughout history, this particular ‘sin’ has been called ‘romantic love.’

The ‘Sin’ of Romantic Love

Sin is a word derived from the Greek - "hamartia," which means ‘error,’ or ‘missing the mark.’ Its meaning also encompasses a ‘fatal flaw.’

If we study some of the great love stories of the world, such as William Shakespeare's ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ The young lovers die by suicide. Romeo drinks poison, and when, after killing Paris and seeing Juliet's seemingly lifeless body, kills himself. Then, when Juliet awakens, she finds Romeo dead and kills herself with his dagger.

The death of Romeo and Juliet

In ‘Tristan and Isolde,’ we also find the story ends in tragedy

The death of Tristan and Isolde. They fall in love after accidentally drinking a love potion meant for King Mark and Isolde. Their affair leads to Tristan's banishment and, ultimately, to his tragic death. Isolde, arriving too late to save him, dies of grief at his side.

In ‘Orpheus and Eurydice,’ we also find the story ends in tragedy.

Orpheus leads Eurydice out of the underworld. The three fates are in the background. In Greek mythology, the three Fates, also known as the Moirai, are goddesses who control fate and destiny. They are Clotho, the Spinner, who begins the thread of life; Lachesis, the Allotter, who measures the thread and determines how long it will be; and Atropos, the Inflexible, who cuts the thread, marking the end of life.

Hades, the Lord of the underworld, abducts Eurydice and takes her to his realm. Her beloved Orpheus travels to the underworld and convinces Hades with music to let him take Eurydice back to the world of the living. Hades tells Orpheus not to look back as he leads Eurydice back to the world of the living. This instruction is crucial, because if Orpheus looks back at her before they have fully exited the Underworld, she will be lost to him forever. However, Orpheus looked back at Eurydice because he feared she wasn't following him as promised and because he was overcome by love and a desire to see her. (See the movie Black Orpheus for an exquisite, more modern-day version of the story set in Rio de Janeiro):

It is the nature of the world: There is no great love story without tragedy, no happiness without sadness, no pleasure without pain, no desire without frustration, and no life without death or loss.

Romantic love is, by its very nature, idealistic and full of desire, and, ultimately, tragic. as it is with the Shah and the architect of the Taj Mahal. For both of them, their desire is inevitably frustrated. This occurs in one form or another for everyone who falls in love. We will inevitably suffer the loss of our loved ones, and they will suffer the loss of us.

This lesson is mirrored in the design of the Taj. This ‘most beautiful building in the world’ is a demonstration, not of fulfillment, but its impossibility in the form of the paradox of romantic love. Romantic love is a ‘Divine’ obstruction, not just because this type of love is ultimately frustrated, but because it is deluding, a veil of illusion, which blinds us to what we do not want: ugliness, mortality, tragedy, and suffering. Yet these qualities, which we seek to avoid, are the very qualities we must allow in order to appreciate what is truly beautiful: Reality, the nature of life, God.

The Trouble with Desire

Desire has been criticized throughout history. Parents criticize and correct the selfish desires of their children. Societies have laws to punish those whose desires would take what is not rightfully theirs or violate the life and liberty of their fellow man. Today, the world and its ecosystem are much imperiled by man’s desire. Mankind is caught in the grip of dangerous possibilities; we seek to accumulate ever more money, possessions, and power while ignoring the consequences of our actions on the survival of the planet and our happiness. Our world punishes us for our selfishness.

The wise have criticized desire, but they go deeper in their understanding; their great insight is that desire for what one does not seem to have is, by its very nature, an expression of suffering. Why? Because desire is the movement of attention from the Source of our existence to one or another object or experience. The wise remind us of our avoidance of True Love. They teach that at the heart, we are always and already full, free, and at peace. When we fail to recognize this, we seek something ‘more,’ some experience, or attainment outside ourselves. Desire is a footprint of the denial of Nature and immersion in suffering.

The truly wise have never made much of idealism. They have made clear that idealism – be it political, religious, social, personal, or interpersonal – is a demand for something that life cannot and will never ultimately provide. Idealism is our attempt to perfect life while ignoring the facts of life. The story of ‘The Man Who Created the Taj Mahal’ is best understood as a ‘monumental’ criticism of the idealism of romantic love as well as a pointing to what lies beyond and through it.

The most important lesson of this ‘criticism’ is that a gateway to the Heart of our existence exists in the human heart itself. The Shah and his architect tasted a vision of the Taj Mahal as the loss of a loved one that wounded their hearts. In the heart-breaking paradox of love and loss, if only for a moment, they attained the heart-broken state of Sama or balance and Realized what is Eternal: they experienced the juxtaposition of romantic love and tragedy, triumph and despair, ascending and descending forces and qualities; this comprised the vision that gave rise to the Taj Mahal.

As we listen to the story of the Taj Mahal from its creation to its aftermath, as we consider its form, the reason the structure was built, and the men who desired and created it, we must be touched not just with romantic sentiments and sweetness but with grief and sorrow. We are called to Sama or balance, just as those who created the Taj Mahal.

Peter on the ghats in Benaras, India, 2004

About the Author

I am a Religious studies scholar, poet, storyteller, Ayurvedic consultant, ghee maker, teacher, and Woodworker living in the foothills of the Himalayas.

In 2004, I graduated from Kalidas Sanskrit University, where I studied Ayurveda. In 2011, I came to live full-time in India, whose ancient culture I had studied in college. All my life, I loved the stories of India, which offer up the Truth of life in such profound, memorable, and delightful stories and forms.

These ancient tales carry the Wisdom of the oldest still-living culture on earth. Impossible to fully understand and endless in their wisdom, they are the vehicles that have brought the Teachings of this land to its generations for eons.

I had been in India only a few years, and already, I was drowning in the abundance of songs one can hear of the great Beings who lived here and the stories they have told.

This is but one of them. . .

What an incredibly well written and interesting story..Thank You Peter..